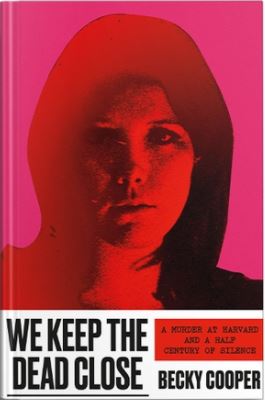

On January 7, 1969, a young Harvard anthropology PhD candidate named Jane Sanders Britton was murdered. There were whispers that the young graduate student was having an affair with a married Harvard professor of archeology. It was said that the death scene was staged in a way that indicated the murderer had knowledge of ancient burial rituals, thus implying a likelihood that he or she was associated with Harvard’s anthropology program. The story ended with the school closing ranks to protect its own. Forty years later, Harvard undergraduate Becky Cooper heard a mythologized, exaggerated version of the still-unsolved crime and, though she dismissed certain aspects as outlandish, felt a kernel of recognition in the power held by Harvard, a centuries-old institution she envisioned as beholden to no one but itself. A year later, when Cooper heard the story repeated and learned that the suspected professor was still teaching at Harvard, she launched a borderline obsessive, ten-year long investigation into the murder, culminating with her recently published book We Keep the Dead Close: A Murder at Harvard and a Half Century of Silence.

As you would expect from a work of investigative journalism, Becky Cooper uncovered a number of suspects through her inquiries, identified through conversations with Jane’s friends, colleagues, or other amateur sleuths with an interest in the case. Much like a real investigation, bits and pieces of these suspects’ lives, backgrounds, potential motives, and relationships with Jane are slowly revealed, eventually eliminating some suspects and leaving others unresolved. While the answer to the question of who killed Jane Britton is the underlying thread of the book, and propels the narrative briskly, it only scratches the surface of the book’s depths.

There is a certain mystique that I associate with Harvard and, given its reputation as one of the preeminent universities in the United States, I naively assumed that, regardless of status, race, gender, or politics, academia was valued above all else. What Becky Cooper unveiled during her research, however, was a culture of blatant sexism, misogyny, and harassment that female graduate students like Jane Britton had to endure with little to no recourse, their academic futures held in precarious balance by men made invincible through their tenure. Radcliffe College, Harvard’s sister school, had just begun conferring Harvard degrees in the early 1960s and the second wave of the women’s rights movement was still in its infancy, so, while it’s unsurprising that the vestiges of a boys’ club mentality still remained at Harvard during Jane Britton’s time, what I found shocking is how long it was allowed to continue, well into the 2000s. Becky Cooper spoke with numerous women denied tenure or driven out long before that time because of some traumatic event. I wonder, what would have awaited Jane in the academic world at Harvard had her life not been cut short too soon? As Cooper put it, “[if] Jane’s story functioned as a kind of cautionary tale, then perhaps it was less about the literal truth of what happened to Jane than it was an allegory about the dangers that faced women in academia… Jane’s story existed, perhaps, to voice injustices that otherwise couldn’t be easily raised.”

Becky Cooper’s dogged requests for public records and her pursuit to keep Jane Britton’s case active is ultimately what helped push the authorities to test the remaining genetic material in the unsolved case. Advances in technology matched DNA from the crime scene to identify Jane’s murderer nearly fifty years later. And while this information provided a measure of closure for Jane Britton’s family and all those affected by her murder, I was deeply unnerved by the reveal. Even in this, though, Becky Cooper found a strange parallelism in the tragedy of Jane’s death and her chosen field of study. Archeology is the study of human history through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains. It’s through this analysis that archeologists, shaped by their own studies, experiences, and history, tell stories of the past; similarly, in the writing of this book and the process of separating myth from fact, Becky Cooper acknowledged her own biases in shaping the narrative of Jane Britton’s story.

“There are no true stories; there are only facts, and the stories we tell ourselves about those facts.”

Discover more from Cook Memorial Public Library District

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Books and More

Tags: Books and More