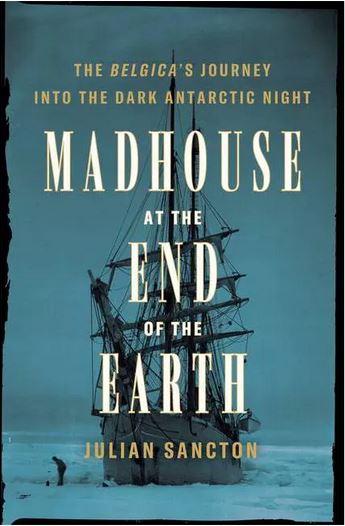

Who doesn’t love a good adventure story? Especially if it’s a story of man pushed to his ultimate physical and psychological limits. Even better is if the tale involves danger, heroics, intrigue, insanity, and betrayal; and what’s best of all is if the story is true. A recently published book that fits the bill on all of these accounts is Julian Sancton’s Madhouse at the End of the Earth: The Belgica’s Journey into the Dark Antarctic Night. This is the true story of an 1897 Antarctic expedition headed by a Belgian commandant whose singular desire to be the first to reach the South Pole hovered like a specter over every decision he made on the ill-fated journey; so much so that, at one crucial point, the commander outright lied to his crew and did something that put all of their lives at risk and drove some to madness. But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the public was voracious for tales from dashing adventurers exploring uncharted territory: the first to discover new species of plant or wildlife, climb a mountain peak, navigate the Congo, or reach the North Pole. For Adrien de Gerlache, his quest for glory centered on charting the largely unexplored continent of Antarctica and being the first to reach the Magnetic South Pole, thereby bringing acclaim to his country and honor to his family. As a member of one of Belgium’s oldest aristocratic families, de Gerlache was eager to contribute to his family’s legacy, but he also bore the heavy weight of expectation that came with such an illustrious name. In his mind, to fail would not just be a personal loss, but one that would diminish centuries of his family’s good name. He feared the censure and judgment of those wealthy and influential patrons who put their faith into backing his bold three-year expedition.

From the start, the expedition was plagued with setbacks. De Gerlache’s vision for the expedition would have Belgium go down in history with a record first while also contributing invaluable scientific data to the fields of zoology, botany, oceanography, meteorology, and terrestrial magnetism. However, finding Belgian scientists qualified and willing to undertake the risky journey, much less hire experienced seamen, proved to be nearly impossible. The crew that de Gerlache ended up with was only half Belgian, with a sprinkle of Norwegians, a Romanian zoologist, Polish chemist and American doctor. This motley crew, with little Arctic experience among them, had yet another major obstacle: the fact that they did not share a common language. Despite these problems and countless others, the intrepid ship Belgica was able to make it about 20 miles further south than the previous Antarctic expedition, but the setbacks they experienced along the way had cost them precious time. This was not the glory de Gerlache envisioned for himself so, despite the looming threat of the months-long polar night, he pressed further south still.

The awesome, unforgiving power of the Antarctic winter combined with de Gerlache’s hubris did force him into breaking one record he never planned to attempt: spending the winter imprisoned in the Antarctic’s frozen sea pack. Imagine seventeen people confined to a ship; seventeen people who didn’t speak the same language; seventeen people who only washed once a week, if that; seventeen people with no other entertainment than to get drunk on occasion; seventeen people forced to eat the same canned mush day in and day out. And think about how it would be, in these conditions, to share the ship’s already confining space with countless rats. Now imagine temperatures so cold that -15 felt balmy; a landscape that seemed to be frozen solid like land but still behaved capriciously like water. To venture beyond view of the Belgica was to risk being lost in the frozen wasteland and tantamount to suicide. Finally, imagine all of this day-in and day-out, months on end, without sunlight. And we thought quarantining was bad.

The resulting physical and mental symptoms experienced by the crew is both fascinating and horrifying. It seems like a miracle that anyone made it out of the ordeal with any shred of sanity left. To this day, NASA uses the experience of the men on the Belgica as a case study for a potential new area of human exploration: manned missions to Mars. It’s clear that with any expedition in which people must share space in close quarters for extended periods of time, the psychological challenges they experience are just as important as the technical ones.

I don’t want to give everything about the book away, so I haven’t even told you the half of it. There are the unique members of the crew: the American doctor who was later accused of being a con artist, convicted of fraud, and sentenced to prison in Leavenworth; the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who went on to achieve his own fame as an explorer. There is also the incredible method the crew used to finally free the Belgica from the pack’s icy grip. If you are looking for a tale that includes narrow escapes from death, harrowing descriptions of the inhospitable Arctic world, man’s incredible ingenuity and will to live, then Madhouse at the End of the Earth will satisfy your every craving for a thrilling adventure.

Discover more from Cook Memorial Public Library District

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Books and More

Tags: Books and More