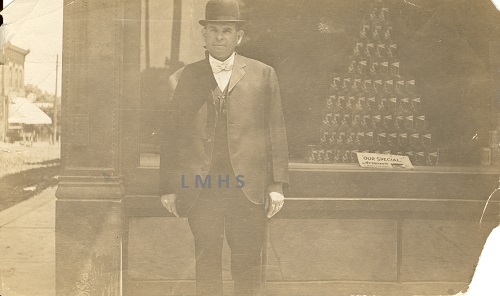

Welcome back to what will be my final post for the year! While I was trying to come up with a topic for this post, I thought “why not make it about something happy?”, and there’s nothing I can think of more uplifting that the story of Dennis S. Limberry. Fire marshal, chief of police, and Thistle commissioner (yes, that’s an actual thing), “Denny” as he was affectionately called by the residents of Libertyville, was a beloved figure in early 20th century Libertyville.

The exact date of Dennis S. Limberry’s birth is a matter of debate, with the 1910 census (where he was counted twice) giving it as December 26, 1865, and the 1920 census giving it as 1871. However, since his birthday was given as December 26, 1860 in his obituary, that is what I will be using for for the purposes of this post.

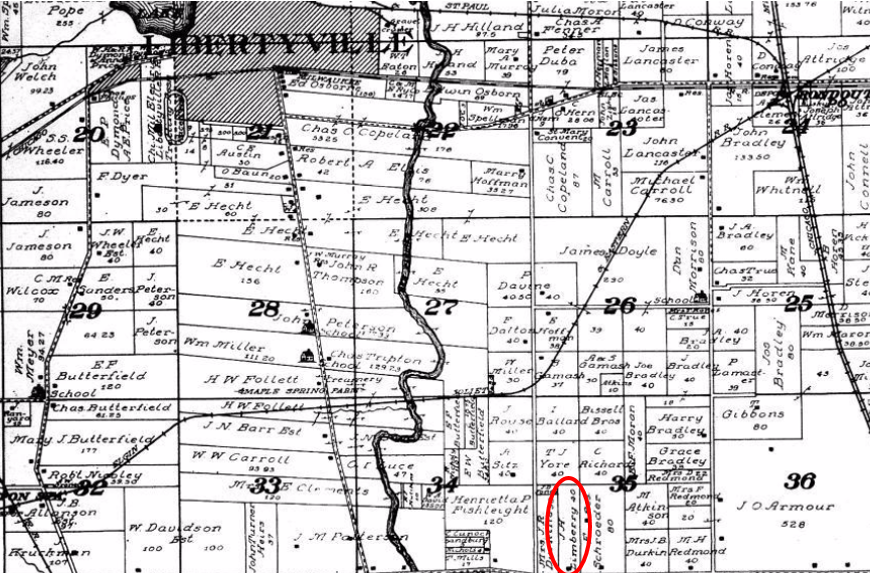

Limberry was born on a farm two miles southeast of Libertyville on what is now Townline Road. His parents, John and Anna Limberry, were both immigrants, his father having been born in Alsace-Lorraine, France, and his mother in Cork, Ireland. Limberry was soon joined by five sisters, Mary (1866), Nellie (1868), Maggie (1870), Agnes (1876), and Sarah, for whom I was unable to find a birth date. In 1877, Limberry’s sister Maggie passed away at the age of seven, and was buried in St. Mary Cemetery in Waukegan. Good-natured and affable, Limberry moved to Libertyville in his late teens, quickly becoming personally acquainted with almost everyone in town, something that would serve him well throughout his career (The Industrial News, 1909).

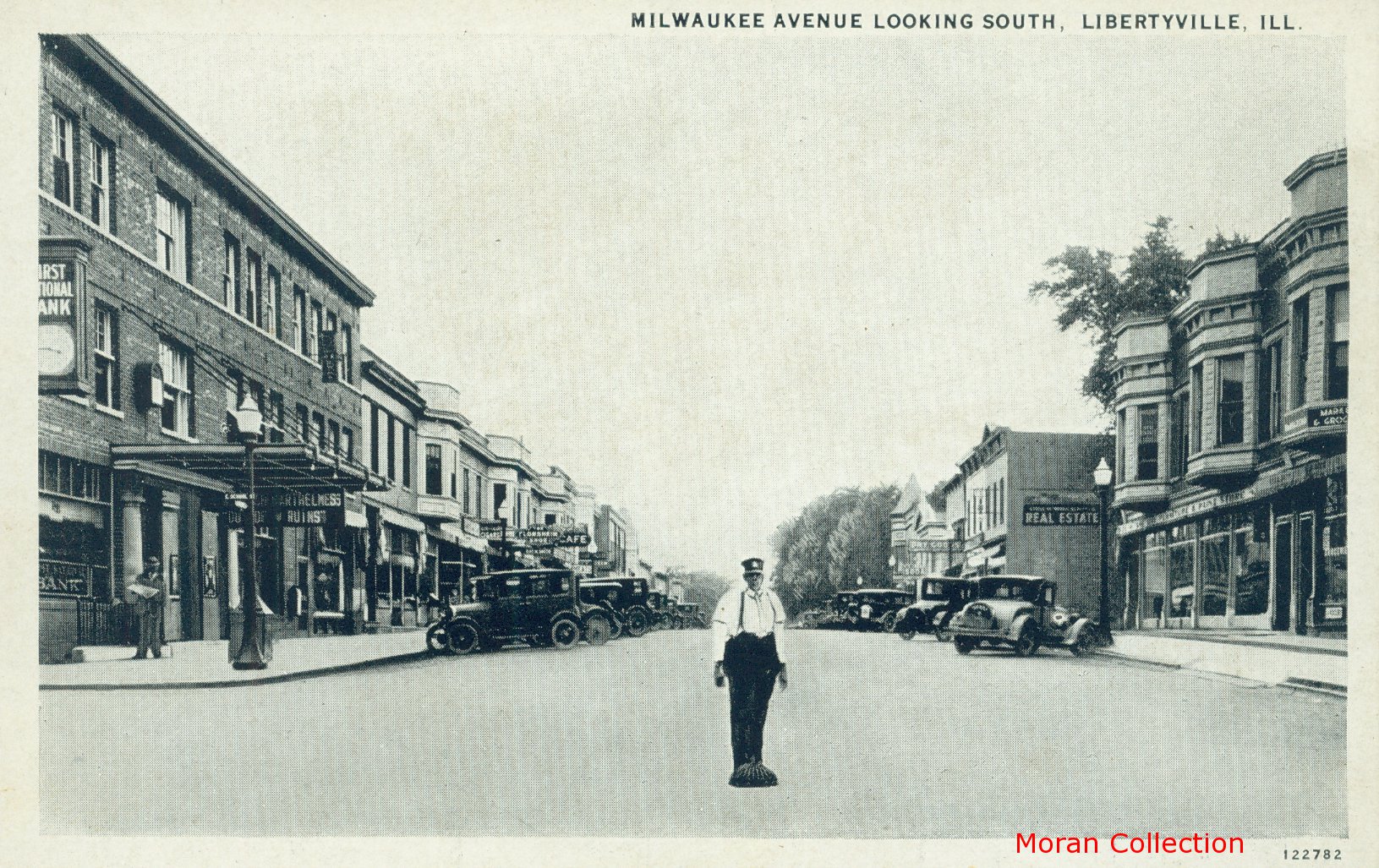

On May 15, 1882, the village voted to incorporate, and at the first meeting of village trustees on June 7, 1882, an ordinance was passed authorizing the creation of a police force. Later that same year, Limberry ran for and was elected town marshal on the Democratic ticket for the first time. Earning $30.00 ($682 today) a month, Limberry’s day started long before the shops were open, raking up all the bits of paper and peanut shells around the hitching posts that dotted Milwaukee Avenue or tending to the flower garden under the village’s original water tower. Later in the morning he acted as crossing guard for students on their way to school. Speaking of children, the use of slingshots by the youth of Libertyville was a major problem, with Limberry confiscating upwards of 200 of the offending articles by at least one estimate (Independent Register 1967, p. 13). However, after giving the child a scolding, Limberry would more often than not send them away with a dime for a movie showing that same night. This was typical of Limberry, and over the course of his career he became well known for his small acts of kindness, from giving needy families coal for cold winter nights, visiting with sick residents, and every Christmas, after the end of World War I in 1918, giving $5 gold coins to fathers who had lost sons in the war.

Limberry was still a police officer however, and like today he had to deal with criminals as well as people suffering from mental illness. In June 1910, Limberry was called when a local farmer discovered an escaped patient from the Cook County Insane Asylum in a forest near his house. A few years later in June 1914, Limberry traveled to Waukegan to arrest a man for public intoxication and days later took the lead in the search for a man suspected of stealing $50 (around $1,223 today) along with a valuable fur coat from his roommate, an employee at the American Steel & Wire Company plant in Libertyville.

Despite the job’s long hours and being constantly on call, Limberry was always looking for new ways to serve his community. In 1896 he was elected as constable, as thistle commissioner in 1902, and deputy sheriff for the county in 1903. By 1912 Limberry had added bailiff, town marshal, and fire marshal (which added an additional $20, or $528 today, a month to his paycheck) bringing his total number of jobs to six. By this time, Limberry, still unmarried at forty-five, was rooming on the second floor of the New Castle Hotel, today’s Runner’s Edge and Eclectic Design Source. Built in 1903 in the 20th Century Revival style and billing itself as a “first class hotel”, boasted “private water works” and “modern plumbing” (Lake County Independent 1903, p.2). Limberry would have rented one of the rooms on the second story by the week.

Because of his lodging situation (Limberry did not have a telephone of his own), so a unique system was devised to let Limberry know if he was needed. The telephone company, which at the time had its offices on the second floor above Lovell’s Drug Store, strung an electric line across Milwaukee Avenue to a tree in Ansel Cook’s yard. When the red light at the center of the line was turned on, Limberry came running, literally in this case as he did not have a horse or car, so for most of his career he made all his rounds on foot, hiring someone to drive him by wagon or by car when he needed to travel further.

Then, on August 20, 1917, Limberry was seriously injured in a car accident while directing traffic on Milwaukee Avenue. Limberry, being his usual self and more focused on his job than his personal safety, had stepped into the street and directly into the path of a car driven by W.A. Baethke, a lumber dealer from Glen Ellyn. Hurled to the pavement, Limberry was dragged for ten to fifteen feet before the stunned driver was able to stop. His chest crushed, Limberry was quickly rushed to Jane McAlister Hospital in Waukegan where doctors John Taylor (Libertyville) and John Foley (Waukegan) worked to save his life. A very dejected Baethke was held on a $5000 bond ($95,619 today) and, after a friend in Libertyville furnished the money for his release, returned home. Luckily, Limberry had always had a strong constitution, and although he would never fully recover from the accident, within days he was resting more comfortably as, according to the Libertyville Independent, the “kiddie(s) depleted the flower crop in Libertyville keeping his room filled with bouquets” (Libertyville Independent p. 4, 1925). Limberry choked with joy, could only say “Hello Children. I love you all” (Libertyville Independent p.1, 1917).

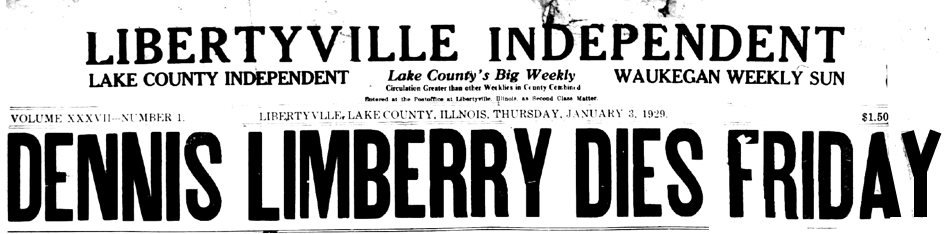

In 1928, after serving the people of Libertyville in one way or another for forty seven years, Limberry became the village’s first chief of police. Now sixty-eight and suffering from rheumatism and a heart condition, he continued to help out around the village where he could, tending the garden of village hall and visiting patients at Condell Hospital. On Friday night December 28, four homeless persons, cold and hungry approached Limberry, begging him for a warm place to stay. Breaking his own rules, he allowed them to stay the night at the jail. Complaining of chest pains Limberry left for the night, promising them a warm breakfast the next morning. The next morning he didn’t come though. Shouting to be let out, they were able to alert two men, who were playing pool in the building next door, to their presence. Officer Frank Druba was dispatched to see what the matter was, and learning that Limberry had not been seen since the night before, he hurried to the New Castle Hotel to check on him. Druba found Limberry in his bed, having passed away in his sleep, and surrounded by over one hundred and fifty Christmas presents, many of them from children.

Limberry’s passing made front page news and his funeral, which was held at St. Joseph’s Church, was attended by almost a thousand people. Students from the grammar and high schools came to pay their respects, along with representatives from other villages and police departments. Over a hundred cars accompanied Limberry to his final resting place in St. Mary’s Cemetery. Having little in the way of family left, at the time of his death Limberry had only five surviving nephews and two nieces spread out across the country, he left a large part of his $10,000 estate to a boy named Edwin Olin, who he had taken an interest in.

I guess the ending of this story is a little bittersweet, but Dennis Limberry, with his small acts of kindness and genuine love of Libertyville and the people who lived there passed on into local legend. So I’ll leave you with the last lines of a poem, appropriately titled Denny’s Gone, written by John DeLong and published in the Lake County Register shortly after Limberry’s passing:

“And in the place where angels are

His joy will be to stand

At crossing fair where children pass,

And smile and wave his hand”

Bye, Johanna. Application for Historic Preservation Landmark Designation. Libertyville, IL, 2016.

Carrol, Charles W. “Law and order established in Libertyville.” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights), June 4, 1986.

“Chief Limberry crushed as he directs traffic.” Libertyville Independent, August 23, 1917. Accessed November 8, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3145985/data?n=3.

“Dennis Limberry: A man marked by history.” Independent Register (Libertyville), October 26, 1967.

“Dennis Limberry is laid to rest.” Lake County Register, January 5, 1929.

“Dennis S. Limberry, village officer.” The Industrial News (Chicago), August 14, 1909.

“John Limberry dies at home of sister on Monday.” Libertyville Independent , February 8, 1917. Accessed November 9, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/2582680/data?n=2.

Lane, Arlene, and Sonia Schoenfield. “Back in the day, Dennis Limberry was Mr. Libertyville.” Libertyvile Review, December 24, 2009.

“Legend of Dennis Limberry.” Libertyville Independent , January 3, 1929.

“Libertyville briefs.” Lake County Independent (Libertyville ), November 12, 1909. Accessed November 7, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3170052/page/5?q=Limberry&docid=OOI.3170052.

“Libertyville preserves past.” Pioneer Press (Chicago), December 30, 1999.

“Libertyvile Township.” Map. In Standard Atlas of Lake County, 27. IL: Geo A. Ogle & Co., 1907.

“Limberry has more jobs than any Lake County man.” Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun (Libertyville), October 4, 1912, sec. 2. Accessed November 13, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3132566/data?n=1.

“Marshal Limberry greets children.” Libertyville Independent, September 20, 1917. Accessed November 27, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3171097/page/1.

“Miller wins close contest.” Independent-Register (Libertyville), April 4, 1902. Accessed November 27, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3169647/page/5.

“The new proctor building.” Lake County Independent (Libertyville), September 25, 1903. Microform.

Photo courtesy of the Cook Memorial Public Library District, the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, and the National Register of Historic Places.

“Seek to find men charged in diamond theft.” Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun (Libertyville), July 24, 1914, sec. 2. Accessed November 9, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3136597/data?n=1.

“Thistle notice.” Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun (Libertyville), July 3, 1908. Accessed November 27, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3169982/page/5?q=Thistle &docid=OOI.3169982.

“Three hurt in auto accident.” Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun (Libertyville), November 5, 1909. Accessed November 9, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3128277/data?n=1.

Discover more from Cook Memorial Public Library District

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History