The library has something to celebrate! 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the Cook Memorial Public Library. The doors of the former residence of Ansel B. Cook opened to the public as a space for books and reading on October 22, 1921 [1]. In the intervening 100 years, library service has changed a lot, but the library’s commitment to the public has never waned.

This is the first of many blog posts over the course of this year that will tell the history of Cook Memorial Public Library . This month’s post will first examine the days in Libertyville when a building full of books available to all was only a dream, and then show just what it took to build the foundation of the institution known as the Cook Memorial Public Library District today.

The history of the library goes back a few decades before 1921. Civic institutions don’t spring up overnight, and Cook Memorial Public Library was no exception. It took several starts and sputters, plus a good deal of resolve and pluck in the citizenry, to even get the idea off the ground.

The mid-1890s was the end of the Gilded Age, which had begun with economic growth and optimism. In Libertyville and the surrounding communities, the beginnings of a hopeful idea flickered. Twice in the 1890s and twice more in the early 1900s, groups of individuals attempted to put together a collection of books, funded by individual subscriptions, that would be available to the community.

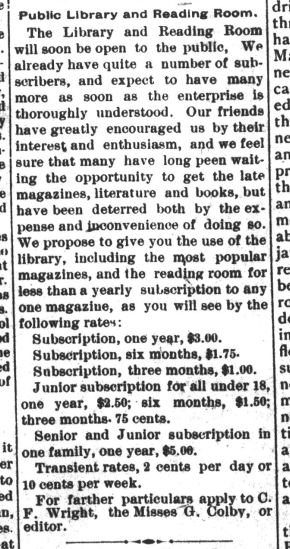

In 1894 several young people (C. F. Wright and sisters Guyneth and Garnet Colby) attempted to get a subscription library off the ground, with a reading room and a yearly subscription of three dollars:

Their attempt was admirable, and further articles later in the year included lists of books in their library and daily hours [2]. In the warm August months, however, the hours of the reading room were cut back due to lack of patronage [3], and eventually this library faded from the public view.

On August 31, 1895 fire broke out on the eastern side of Milwaukee Avenue and destroyed buildings along several blocks. It’s possible that the folks of Libertyville were intent on rebuilding their town and didn’t think much about a public library for a few years. In November 1897 a single article mentioned a “Parmelee circulating library” that was installed in F.B. Lovell’s drug store at 426 North Milwaukee Avenue, but no other reference to this book collection followed [4].

The local paper was one of the greatest supporters of the idea of a public library in Libertyville. On May 25, 1894 the editors of the Lake County Independent had written an impassioned plea for a public library in Libertyville [p5], and they pulled no punches in calling out who could afford to give the money to start it. After a litany of ways that the village had spent significant amounts of money in the past they continued,

” ‘Cook’ Library”? By this time Ansel Cook had retired from his successful stone masonry business in Chicago and was living at his home in Libertyville on Milwaukee Avenue. Perhaps the newspaper article started him thinking about his legacy. As a previous ShelfLife blog post has noted,

“Not six months later, Ansel’s will, dated Dec 15, 1894, made provisions for the ‘building of a Memorial Hall in the village of Libertyville, Lake County, Illinois, to be known as the A. B. Cook Memorial Hall, with a free-library therewith’ upon the death of his wife Emily Barrows Cook.” [6]

Mr. Cook died in 1898. There was a large mortgage on the property which Emily paid off with her own money, keeping the property for a future library and park, in accordance with her husband’s wishes and with which she was in total agreement. [7]

In 1903 Mrs. Cook’s real estate transactions became public along with the fact that the Cook property had been designated for a free public library. The village of Libertyvile was grateful in anticipation, declaring, “few realize just what a great benefactor the late A. B. Cook will prove to Libertyville, the matter having come to be generally regarded improbable of taking substantial shape.” [8]

Another event of 1903 that would have a future impact on the existence of a library in Libertyville was the birth of the Alpha Club. Women in Libertyville formed the Alpha Club as a study group; they gathered to read and discuss assigned texts on American, English, and German literature; American history as well as the histories of England, Germany, Italy; and social and cultural topics such as immigration, psychology, and art. Because of their interest in literature, the women of the Alpha Club started their own subscription library, but at this time it was for members only [9].

In the new century, the idea of a library for the public in Libertyville would not go away. In 1904 the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) set up a reading room over the Heath furniture store [10] at 535 N. Milwaukee Avenue.

Another article in 1905 listed some of their books but no further mention of the WCTU reading room followed [11].

In the late fall of 1906 the people of Libertyville seemed so desperate to have a library that they considered establishing a “Tabard Inn Library,” whereby, for a fee, members could buy and exchange books from a free-standing set of bookshelves [12].

It is possible that “the organizer” of the potential Tabard Inn Library mentioned above was not met with enough smiles and memberships when he came knocking on Libertyville doors, because this idea was never mentioned again in the papers. Or perhaps the organizer never came; Seymour Eaten, the founder of the Tabard Inn Library system, declared bankrupcy in 1905 [13]. Would Libertyville ever get the library that it needed?

Libertyville was not the only village in the county with aspirations for a library. In 1901 Waukegan accepted the gift of a Carnegie library near their downtown [14]. Highland Park also was the beneficiary of an Andrew Carnegie library in 1905 [15]. In 1907 the Women’s Club of Grayslake set up a library collection in the Godfrey store downtown [16]. But Libertyville still had no library.

In early 1905 a “library extension” bill which would provide communities throughout the state with library collections gained popularity among the citizenry of the state, particularly the Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Teachers’ Institute, the Farmers’ Institute, and the Illinois Library Association; however, it wasn’t until 1909 that the General Assembly passed a law which created the Illinois Library Extension Commission. The purpose of this commission was to establish and support free public libraries throughout the state. [17].

Eventually, everything came together for Libertyville. The Progressive Era, with its ideals of women’s rights and education for all, fanned the idea of a Libertyville library into a flame. In 1910 the Alpha Club modified their members-only library and opened it to the public, for a one dollar a year subscription [18].

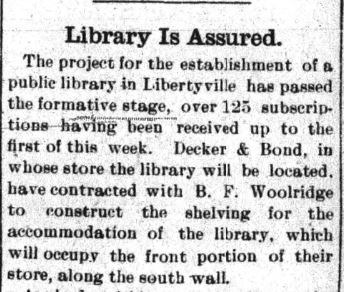

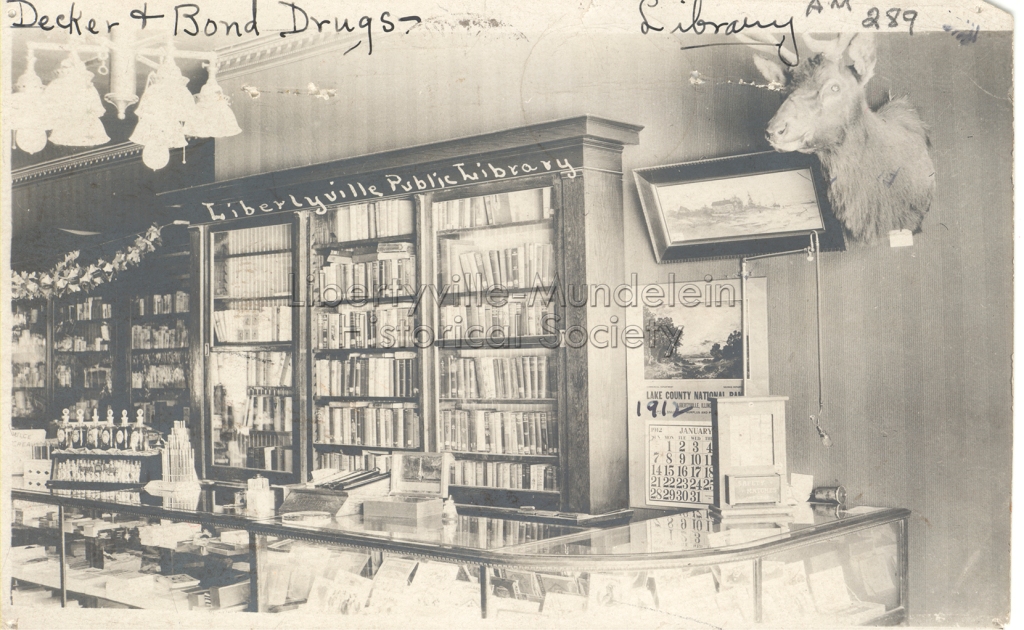

In the fall of 1910 Alpha Club members and civic leaders Mabel MacGuffin, Clara Colby, Edith Warren and Laura Taylor convinced over 125 people to subscribe to their library [19]. They went to Chicago and bought 180 books of fiction for the town library collection. Fifty books of reference, science and business were to be supplied by the state library in Springfield on a rotating basis [20]. The Decker and Bond drugstore, located where Edie’s Boutique is today, provided space for the books and Benjamin Woolridge, a local carpenter, built shelves to hold the book collection [21].

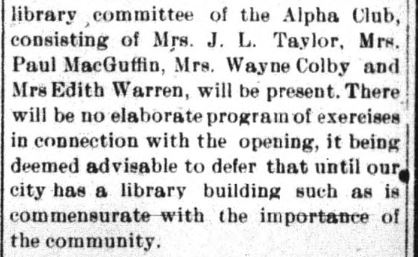

Despite the number of subscribers, the support of the community, and the industry of the Alpha Club Library Committee, there was a sense that Libertyville could do better. The library was set to open on Saturday, December 10 at 2 p.m, but there were no formal opening ceremonies. The committee deemed it best to wait until “our city has a library building such as is commensurate with the importance of the community” [22].

December 9, 1910, p. 5.

The library opening was nevertheless a success [23]. Under the stewardship of the Alpha Club, the library collection grew and they even produced a catalogue of all the books in the collection [24]. From time to time a list of new books at the library was published in the newspaper and the public was encouraged to keep the lists for further reference.

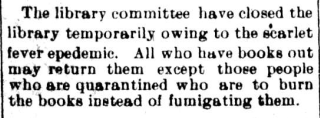

The library experienced a few bumps as well, including having to temporarily shut down because of a public health threat in 1911 [25].

In just a few short years the bookshelves in the Decker and Bond Drugstore were bursting to overflowing. (This would become a theme throughout the library’s history.) The book collection had grown to over 600 volumes and the drug store shelves weren’t big enough to hold them all [26]. It was time to find a new home.

Then in 1913 Libertyville built a new Village Hall, thanks to the first village referendum in which women were allowed to vote [27]. Libertyville stalwarts Mabel MacGuffin and Clara Colby had voted in favor of building a new village hall; now that building would also house the library that their Alpha Club ran. The Alpha Club moved their library into the village hall in December of 1914. For the first time, the library had hours of operation, open Tuesdays and Saturdays from 2:30 to 5:30 p.m. and 7 to 9 p.m. [28]. The library was located in the front of the village hall on the second floor, a southward-facing room with plenty of natural light for reading [29].

At this point the library was still supported only by subscriptions, so the Alpha Club hosted fundraisers to supplement their subscription income. In 1915 they hosted an antique exhibit that displayed, among other items, furniture, “a table spoon which was brought from Europe in [sic] the Mayflower,” sampler quilts and “many fancy articles,” plus the Wide Awake banner that Libertyville men had won at a Lincoln rally in 1860 [30]. In 1917 the Alpha Club arranged two musical concerts that featured a harpist, a violinist, a pianist and vocalists [31]. The year before, another Libertyville Club, the Merry Makers, donated $50 to the library [32] which the Alphas gratefully received [33].

The Alpha Club continued to develop the library by adding more books and encouraging villagers to subscribe. They always put out a suggestion at Christmas that a subscription made a wonderful present [34].

On December 7, 1919, Mrs. Emily Cook, wife of Ansel B. Cook, passed away. In her will she left her home and property to the village of Libertyville, to be used as a park and public library, fulfilling the expressed wishes of her husband Ansel B. Cook [35].

The little book collection that started out first as a hopeful idea and then as a few shelves of books in a drug store now had the promise of a permanent home. It would be more than a year, however, before the books were finally settled on shelves in the Ansel B. Cook house on Milwaukee Avenue.

Notes

1. Minutes of Cook Memorial Library Board of the Village of Libertyville, April 1921 to July 1924 Inclusive, November 1, 1921

2. Lake County Independent, June 22, 1894, p. 5.

3. Lake County Independent, Aug 3 1894 p5and 31, 1894 p. 5.

4. Lake County Independent, November 12, 1897, p. 5.

5. Lake County Independent, May 25, 1894, p.5.

6. Who Was Ansel B. Cook? Part 3, ShelfLife, https://shelflife.cooklib.org/2017/02/10/who-was-ansel-b-cook-part-3/, accessed March 22, 2021.

7. Lake County Independent, July 17, 1903, p. 5.

8. Ibid.

9. History of the Alpha Club by Mavis Wike from Cook Memorial Public Library Local History File, “Libertyville Women’s Club” folder.

10. Lake County Independent, November 11, 1904 , p. 5.

11. Lake County Independent, February 10, 1905, p. 5.

12. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, September 7, 1906, p. 5.

13. The Tabard Inn Library, The Library History Buff, http://www.libraryhistorybuff.com/tabard-inn.htm. accessed March 22, 2021.

14. Lake County Independent, March 22, 1901, p. 1.

15. A History of the Highland Park Public Library, Highland Park Public Library, https://www.hplibrary.org/history-5325, accessed March 22, 2021.

16. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, October 25, 1907, p. 3.

17. Sorensen, Mark, The Illinois State Library, 1870 – 1920, p. 96. https://www.lib.niu.edu/1999/il990294.html, accessed March 22, 2021.

18. paper on Alpha Club from local history files

19. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, November 18,1910, p. 5.

20. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, Noember 25, 1910, p. 5.

21. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, November 18,1910, p. 5.

22. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, December 9, 1910, p. 5.

23. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, December 16, 1910, p. 5.

24. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, March 7, 1913, p. 4.

25. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, September 29, 1911, p. 5.

26. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, November 13, 1914, p. 4.

27. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, July 11, 1913, p. 1.

28. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, December 11, 1914, p. 4.

29. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, November 13, 1914, p. 4.

30. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, April 16, 1915, p. 2.

31. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, February 8, 1917, p. 1.

32. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, August 17, 1916, p. 1.

33. Lake County Independent and Waukegan Weekly Sun, September 14, 1916, p. 1.

34. Libertyville Independent, December 21, 1916, p. 5.

35. Libertyville Independent, December 11, 1919, section 2, p. 5.

Discover more from Cook Memorial Public Library District

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History