Welcome back to my somewhat belated second installment on the history of the Native American peoples of Lake County! When we left off in my last post, it was the early 1600’s. In what would become Illinois, the Inoca Confederation had risen to become the most powerful tribal group, while on the East Coast of North America, French, Dutch, and British traders, missionaries, and explorers were beginning to make their presence felt. Despite being few in number, by introducing diseases that ravaged the Native peoples and using historical animosities between tribes to use them as proxy soldiers in wars against other colonial powers, these new settlers would eventually win out, setting the stage for the eventual founding of Libertyville.

The late 1610s saw the establishment of European trading posts, mainly Dutch and British, along the Hudson and Delaware rivers, which quickly began selling European goods to the Haudenosaunee, better known to us as the Iroquois Confederacy, in exchange for beaver pelts that they sold at a premium in European markets. Founded around 1142 CE by the Great Peacemaker, it was comprised of five (later six) tribes,including the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk), Onöñda’gaga’, Onyota’a:ka (Oneida), Gayogohó:no’ (Cayuga), and Seneca, with the Skarù:ręˀ (Tuscarora) being accepted into the confederation in 1722. As Dutch and British traders, allied with the Haudenosaunee, consolidated their control over the fur trade on America’s East Coast, French fur trappers began to explore the continent’s interior, making their own Native American allies and bringing the fur trade inland. Among these was Louis Jolliet, a fur trader who, with the Jesuit missionary Jacques Marquette, established trade relations with the Ojibwe, becoming the first Europeans to winter in what would become Chicago in late 1674.

By the 1640s, with European diseases devastating their villages and their hunting parties returning with fewer and fewer beaver pelts, the increasingly desperate Haudenosaunee began attacking the French-allied tribes to secure their hunting grounds. Sensing an opportunity to disrupt the French fur trade, Dutch traders sold the Haudenosaunee guns, leading in early 1648 to the beginning of the Beaver Wars. The Beaver Wars, which would eventually spread all the way to western Illinois in 1655, was not the only instance of Europeans using their native allies as proxies in their struggle for dominance of the fur trade in America. The 17th and 18th centuries saw a series of conflicts involving French and British allied tribes including the Pequot War (1636), King Philip’s War (1675–1678), and the French and Indian War (1754–1763). These conflicts caused mass dislocations, with the tribes like the Neshnabé, Niswi-mishkodewin, Meshkwahkihaki, and Kiwikapawa (Kickapoo) fleeing West to Illinois in search of safety, where they eventually settled near Lake Michigan.

Even as the Inoca struggled to deal with the influx of refugees on the one side and near constant attacks by the French-allied Haudenosaunee on the other, they found themselves dealing with the increasing number of European missionaries and traders living amongst them. In 1675, Jacques Marquette founded the Mission of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin near what is today Utica. Five years later on January 5, 1680, the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle along with Henri de Tonti, erected Fort Saint Louis du Rocher, located in what is today Peoria, Illinois. The fort quickly attracted refugees from the Beaver Wars, including members of the Kaskaskia, Shaawanwaki, and Muhhehuneuw (Mohicans) who established villages near the fort for protection. In 1695, the French established another trading post on a bluff overlooking Lake Michigan in what would become Waukegan. Called Little Fort, its remains would be rediscovered by settlers in 1835, by which time all that remained were some earthworks and a few decaying timbers.

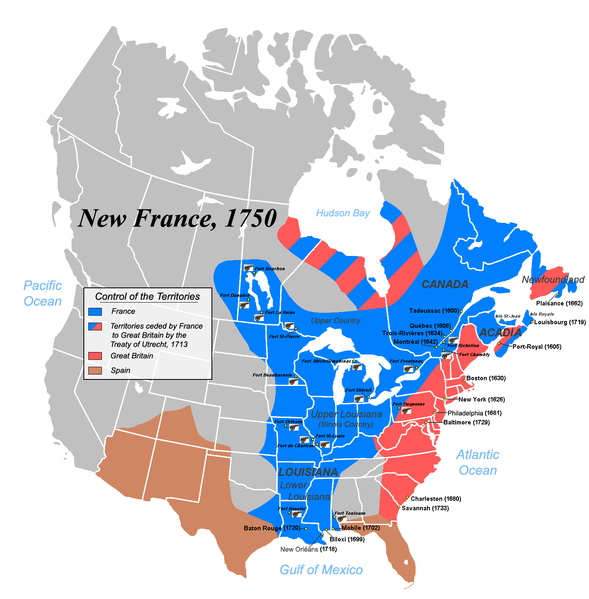

However, by the late 17th century the influence of the French in North America began to weaken. Following the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), on February 10, 1763 the colonial powers signed the Treaty of Paris, giving the British control over Illinois. They had little time to enjoy their new territories however, as little more than a decade later, the British would once again find themselves fighting on the continent, this time against their own colonists.

During the American Revolutionary War a number of tribes, including the Kanien’kehá:ka, Gayogohó:no, and Seneca, sided with the British, while the Onyota’a:ka sided with the colonists. While a majority of the fighting occurred on the East Coast, in July 1778 Brigadier General George Rogers Clark led 175 men into Illinois to capture British forts and settlements. After a series of successful campaigns, on July 4, 1778, Clark claimed Illinois for the Commonwealth of Virginia, renaming it Illinois County, Virginia (it would eventually be incorporated into the Northwest Territory by congress in 1787).

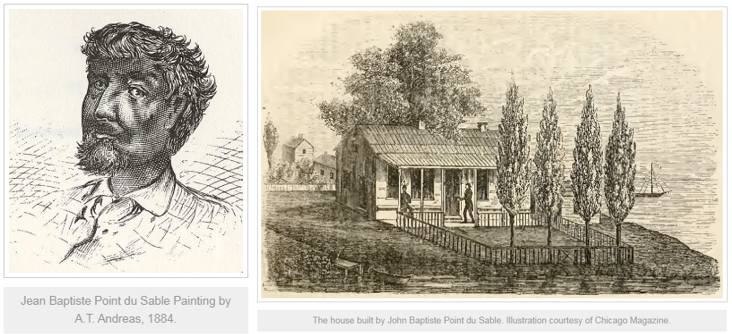

Later, on May 10, 1790, a clerk named Hugh Heward, who was traveling through Illinois, wrote in his journal about stopping at the home of wealthy trader named Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. Born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, Baptiste had settled near the mouth of the Chicago River in the 1780s, becoming the first permanent non-native resident of what would be Chicago. Building a spacious log cabin, which included fine furniture and paintings, Baptiste went on to marry a Native woman named Kitiwaha, with whom he had two children, and establish a lucrative trading post before selling his land in 1800 and moving to Spanish Louisiana (now St. Charles, Missouri).

By the beginning of the 19th century, the tribes of Illinois, devastated by decades of war, European diseases, and confronted with ever encroaching American settlers, were quickly finding themselves running out of options. Left with few choices, in 1816 a group of Neshnabé signed a land cession treaty with the United States, which included what would become Lake County, in exchange for $12,000 in cash, $12,000 in goods, and an annual delivery of 50 barrels of salt. This sale was only one of many land cession treaties, as tribes like the Inoca and oθaakiiwaki (Sac) struggled to retain what little sovereignty they had by selling off the very land they lived on. Sadly, all their efforts were in vain. On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. The act was part of a systematic effort to remove Native American tribes, referred to by President Jackson in his speech to Congress as a “few savage hunters”, from land desired by settlers.

It was against this backdrop that on September 26, 1833, U.S. government officials, soldiers, and land speculators, along with an estimated three thousand Native Americans, including Billy Caldwell, a half-Native fur trader who represented the Council of the Three Fires, met to sign the Second Treaty of Chicago. The treaty ceded over 5 million acres of land in northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, Indiana, and southwest Michigan, with the displaced tribes being resettled west of the Mississippi River. The treaty was ratified by Congress, and near the end of August 1835, 800 Neshnabé men gathered on the north bank of the Chicago River, across from Fort Dearborn for a last show of defiance. For that whole, hot day the grieving dancers danced the last recorded war dance in the Chicago area, passing down present-day Wacker Drive, passing the Sauganash Hotel, named after Billy Caldwell (his Neshnabé name Sauganash, translated as “one who speaks English”). Within a month, a military guard escorted some 700 Neshnabé out of Illinois leading to what would become known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death, a 660 mile trek during which more than 150 Neshnabé died. At this same time, although settlers were officially prohibited from settling the land until August 1836, by spring 1835 settlers like Mundelein’s Peter Shaddle and Libertyville’s George Vardin were already living on the recently vacated land. More settlers would follow, and the Libertyville would be officially founded on July 4, 1836.

Today, there are still a few people of Native American descent living in Lake County. This year, they and others from Neshnabé diaspora will hold the 25th Annual Potawatomi Trails Pow Wow in Shiloh Park in Zion (August 25-26th if you’re interested). And if you want to know more about the history of the Native American peoples of Lake County, I would highly suggest a visit to the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston, without whose help this post wouldn’t have been possible. Additionally, Dakota Wind’s excellent blog The First Scout is a great source of information about Native American history in general and the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ in particular. Anyway, it might be a while before my next post, but I hope you’ll join me next time when I cover the history of the Naval Station Great Lakes!

Today, there are still a few people of Native American descent living in Lake County. This year, they and others from Neshnabé diaspora will hold the 25th Annual Potawatomi Trails Pow Wow in Shiloh Park in Zion (August 25-26th if you’re interested). And if you want to know more about the history of the Native American peoples of Lake County, I would highly suggest a visit to the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston, without whose help this post wouldn’t have been possible. Additionally, Dakota Wind’s excellent blog The First Scout is a great source of information about Native American history in general and the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ in particular. Anyway, it might be a while before my next post, but I hope you’ll join me next time when I cover the history of the Naval Station Great Lakes!

A Battle of the French-Indian War. In Wikimedia Commons. August 16, 2015. Accessed June 12, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Battle_of_the_French-Indian_War.jpg.

“American Expansion.” Indians of the Midwest. Accessed May 31, 2018. http://publications.newberry.org/indiansofthemidwest/people-places-time/eras/american-expansion/.

Andreas, Alfred Theodore. Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable. 1884. Kankakee Community College. In Archive.org. March 15, 2010. Accessed June 4, 2018. https://archive.org/details/historyofchicago01inandr.

Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 18th pt 2. U. S. Govt. Print. Off, 1895. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/annualreportofbu182smit.

“An Unsettling Legacy: The War of 1812 and the Removal Treaties of the 1830s.” Citizen Potawatomi Nation. November 6, 2013. Accessed May 10, 2018. http://www.potawatomi.org/an-unsettling-legacy-the-war-of-1812-and-the-removal-treaties-of-the-1830s/.

Axelrod, Alan. A Savage Empire: Trappers, Traders, Tribes, and the Wars That Made America. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2011.

Barr, Daniel P. Unconquered: The Iroquois League at War in Colonial America. Modern Military Tradition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006.

Kinzie House. 1857. Chicago Magazine. In Wikimedia Commons. September 7, 2010. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kinzie_House.png.

Pequot war. Unknown. Library of Congress. Wikipedia. May 28, 2018. Accessed June 5, 2018. https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pequot_War.jpg.

Lepage, J.F. “Map of the New-France about 1750.” Map. Wikimedia Commons. June 24, 2007. Accessed June 5, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New-France1750.png.

Marquette, Jacques, and Liebaux. Carte de la découverte faite l’andans l’Amérique septentrionale. [S.l., ?, 1681] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003627092/.

Nast, Thomas. “The Great White Father.” Cartoon. American Encounters. Accessed June 12, 2018. http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/american-encounters/case11/jackson.jpg.

O’Neill, Charles E. “Gravier, Jacques.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Accessed May 10, 2018. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=821.

Peters, Richard. Treaties between the United States and the Indian tribes, Vol. 7. United States Government Publishing Office, 1846. Accessed May 10, 2018. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampagecollId=llsl&fileName=007/llsl007.db&recNum =4 .

Petterchak, Janice. Historical Illinois: An Illustrated History. San Antonio, TX: Historical Publishing Network, 2005.

Quaife, Milo M. Checagou From Indian Wigwam To Modern City 1673-1835. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 1933. Accessed May 10, 2018. https://archive.org/details/checagoufromindi001651mbp.

Reardon, Patrick T. “Chicago’s Trail of Tears: Potawatomi Warriors’ 1835 Dance Marked Eviction.” Chicago Tribune, August 24, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2018. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/commentary/ct-potawatomi-tribe-chicago-history-flash-perspec-0828-md-20160825-story.html.

Searcy, Trevor, and Al Wolf. Potawatomi Trail of Death Marker. July 18, 2010. Sidney. In The Historical Marker Database. July 19, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2018. https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=118208.

Thunder, Blue. Blue Thunder Winter Count. 1785. State Historical Society of North Dakota. In The First Scout. December 11, 2015. Accessed June 14, 2018. http://thefirstscout.blogspot.com/2015/12/the-blue-thunder-or-yellow-lodge-winter.html.

White Trader with Ojibwa Trappers, Ca. 1820. 1820. Newberry Library. In Indians of the Midwest. Accessed June 12, 2018. http://publications.newberry.org/indiansofthemidwest/people-places-time/eras/fur-trade/.

Winter, George. Potawatomi Emigration, 1838. 1838. Newberry Library. In Indians of the Midwest. Accessed June 12, 2018. http://publications.newberry.org/indiansofthemidwest/people-places-time/eras/american-expansion/.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History